Optimal Model Performance

Photo by Christophe Hautier on Unsplash

Photo by Christophe Hautier on Unsplash

Some Theory

In this short article, I will take advantage of the latest work on statistical learning theory to discuss why perfect data fit is not necessarily what one should aim for. We shall investigate how the prediction error changes for a polynomial regression when increasing the model complexity and the number of training examples. But first, let us talk about the loss and the risk.

Loss and Risk

Suppose we know the predictors

Squared error loss and the optimal risk

One of the most common loss functions is the squared error loss. As the name suggests, it is simply the square of the difference between

Empirical Risk

All is nice and clear, and we have our solution. However, we do not know the joint distribution of

How it works in practice

Set up

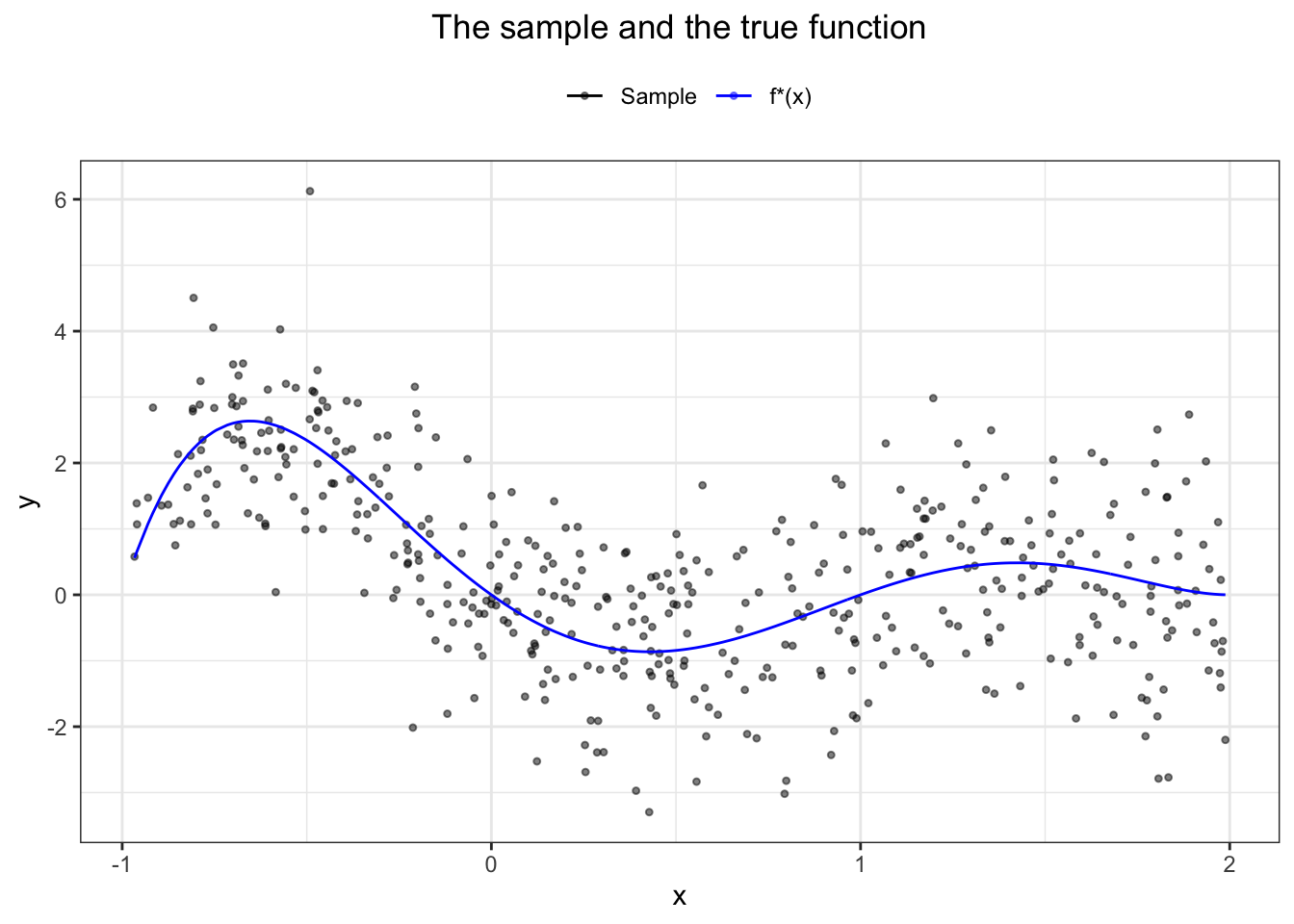

Suppose the “true” function (in reality not available to us) of one predictor is

library(tidyverse)

f_star = function(x){return((x-2)^2*(x-1)*x*(x+1))}

set.seed(1)

x = runif(450, -1, 2)

observations = f_star(x) + rnorm(450, 0, 1)

sample = data_frame('x' = x, 'y' = observations)

true_values = data.frame('x' = x, 'y' = f_star(x))

ggplot(sample, aes(x, y, colour = "Sample")) +

geom_point(alpha = 0.5, shape = 20) +

geom_line(data = true_values, aes(colour = "f*(x)")) +

scale_colour_manual("",

breaks = c("Sample", "f*(x)"),

values = c("black", "blue")) +

theme_bw() +

labs(title = "The sample and the true function") +

theme(plot.title = element_text(hjust=0.5), legend.position = "top") What is the estimated risk of

What is the estimated risk of

sum((sample$y - f_star(sample$x))^2) / length(sample$x)## [1] 1.099824This number is not coincidental. Previously, we showed the existence of the irreducible error due to randomness in

How do the prediction error change when the complexity of the model changes?

Model Complexity

Imagine that we do not know

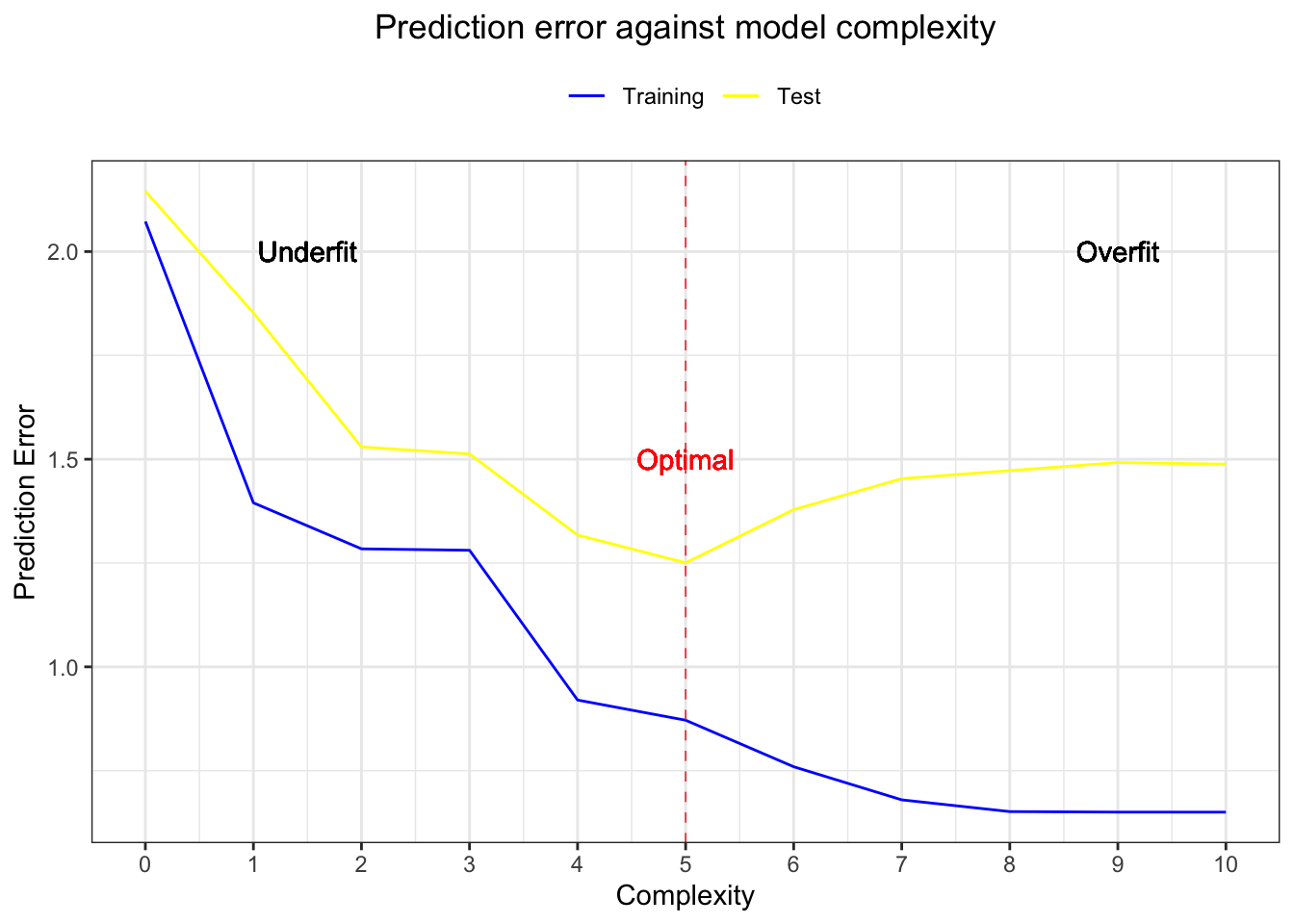

We train 11 models of increasing complexity, starting from a model of just an intercept up to the one with terms up to and including

train = sample[1:40, ]

test = sample[41:450, ]

# Getting empirical risks given a regression

get_errors <- function(reg){

pred_test <- predict(reg, test[,1])

train_error <- sum((reg$residuals)^2) / 40

test_error <- sum((test[,2] - pred_test)^2) / 410

return(c(train_error, test_error))

}

# These will store our outcomes

training_outcomes = c()

testing_outcomes = c()

# Regression with just an intercept

reg0 <- lm(y ~ (1), data = train)

training_outcomes[1] = get_errors(reg0)[1]

testing_outcomes[1] = get_errors(reg0)[2]

# Polynomial regressions of increasing complexity

for (i in 1:10){

reg <- lm(y ~ poly(x, i), data = train)

training_outcomes[i+1] = get_errors(reg)[1]

testing_outcomes[i+1] = get_errors(reg)[2]

}

complexity <- seq(0,10)

outcomes = data.frame(cbind(complexity, training_outcomes, testing_outcomes))

# Plot the results

ggplot(outcomes, aes(complexity, training_outcomes, colour = "Training")) +

geom_line() +

geom_line(aes(complexity, testing_outcomes, colour = "Test")) +

theme_bw() +

scale_x_continuous(labels = as.character(complexity), breaks = complexity) +

labs(title = "Prediction error against model complexity",

x = "Complexity", y = "Prediction Error")+

theme(plot.title = element_text(hjust=0.5), legend.position = "top") +

geom_text(x = 1.5, y = 2, label = "Underfit", inherit.aes = FALSE) +

geom_text(x = 9, y = 2, label = "Overfit", inherit.aes = FALSE) +

geom_text(x = 5, y = 1.5, label = "Optimal", inherit.aes = FALSE, colour = "red") +

geom_vline(xintercept = 5, linetype = "dashed", colour = "red", size = 0.25) +

scale_colour_manual("",

breaks = c("Training", "Test"),

values = c("blue", "yellow"))  When the models’ complexity is low, we can see that both the training and testing sets generate significant errors. The model is not complex enough to capture the patterns in our data, i.e. we underfit. The more complex the models become, the smaller the errors on the training set - we fit the data more and more until we fit perfectly (including the noise, which is, of course, undesirable). On the other hand, the errors of the testing set become smaller up to the optimal point, where they start to increase again because our model fits the noise and does not generalise well, i.e. we overfit the data.

When the models’ complexity is low, we can see that both the training and testing sets generate significant errors. The model is not complex enough to capture the patterns in our data, i.e. we underfit. The more complex the models become, the smaller the errors on the training set - we fit the data more and more until we fit perfectly (including the noise, which is, of course, undesirable). On the other hand, the errors of the testing set become smaller up to the optimal point, where they start to increase again because our model fits the noise and does not generalise well, i.e. we overfit the data.

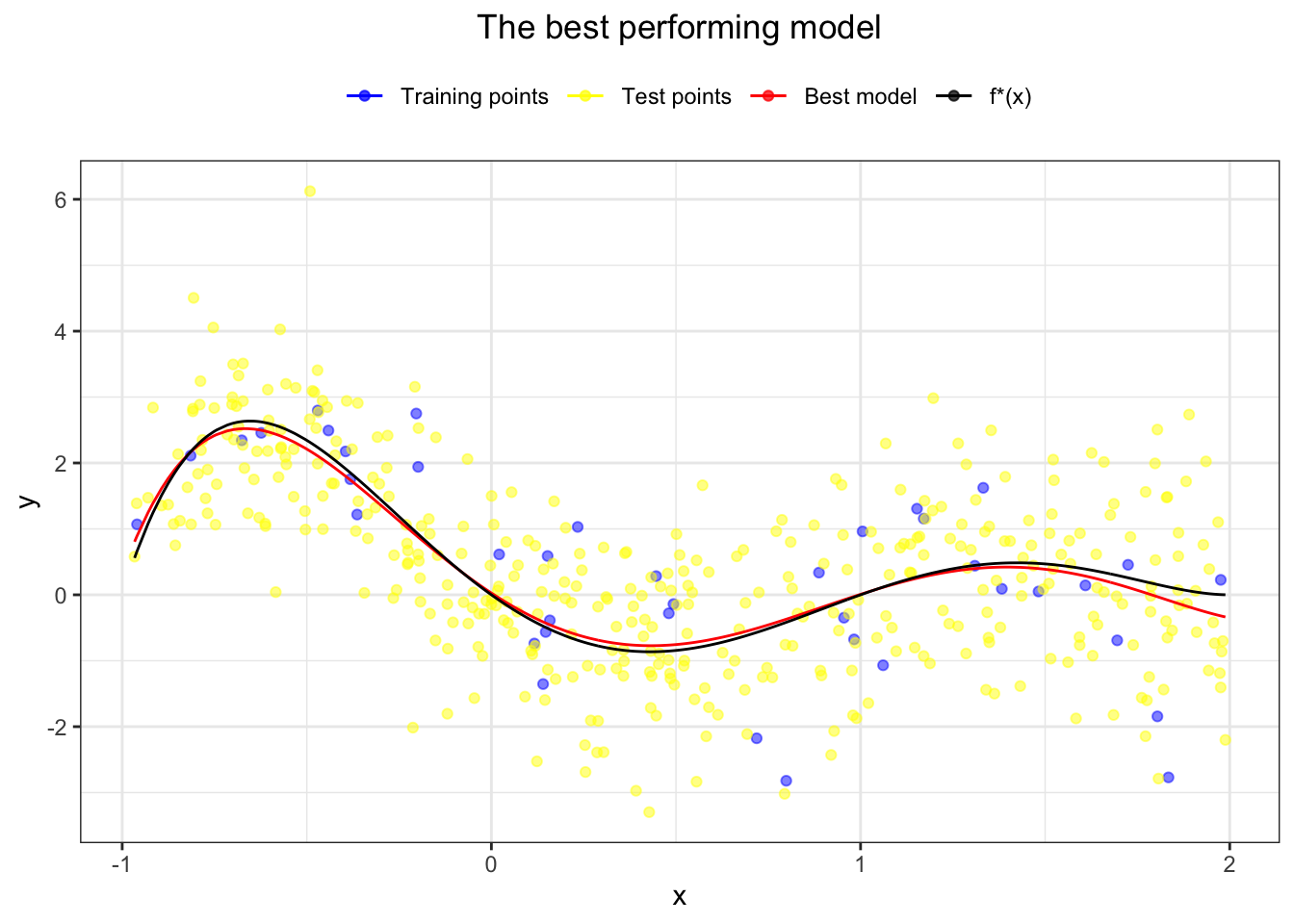

The middle area is the sweet spot - the balance between accurate training fit and good generalisation over the testing set. It is therefore not surprising that the best performing model (giving the smallest test error) is the one of order 5 - the same as our “true” function

Let’s see how our newly found regression compares to the actual

best_reg_points <- data.frame('x' = sample$x,

'y' = lm(y ~ poly(x, 5), data = sample)$fitted.values)

ggplot(train, aes(x, y, colour = "Training points")) + geom_point(alpha = 0.5) +

geom_point(data = test, aes(x, y, colour = "Test points"), alpha = 0.5) +

geom_line(data = best_reg_points, aes(x, y, colour = "Best model")) +

geom_line(data = true_values, aes(x, y, colour = "f*(x)")) +

theme_bw() +

scale_colour_manual("",

breaks = c("Training points", "Test points", "Best model", "f*(x)"),

values = c("blue", "yellow", "red", "black")) +

labs(title = "The best performing model") +

theme(plot.title = element_text(hjust=0.5), legend.position = "top") Not bad! Our model fits very well and often overlaps the “true” function

Not bad! Our model fits very well and often overlaps the “true” function

Note the danger of extrapolation! The regression we found fits well only within the defined region, and we have no reason to assume it will look like

Training Samples

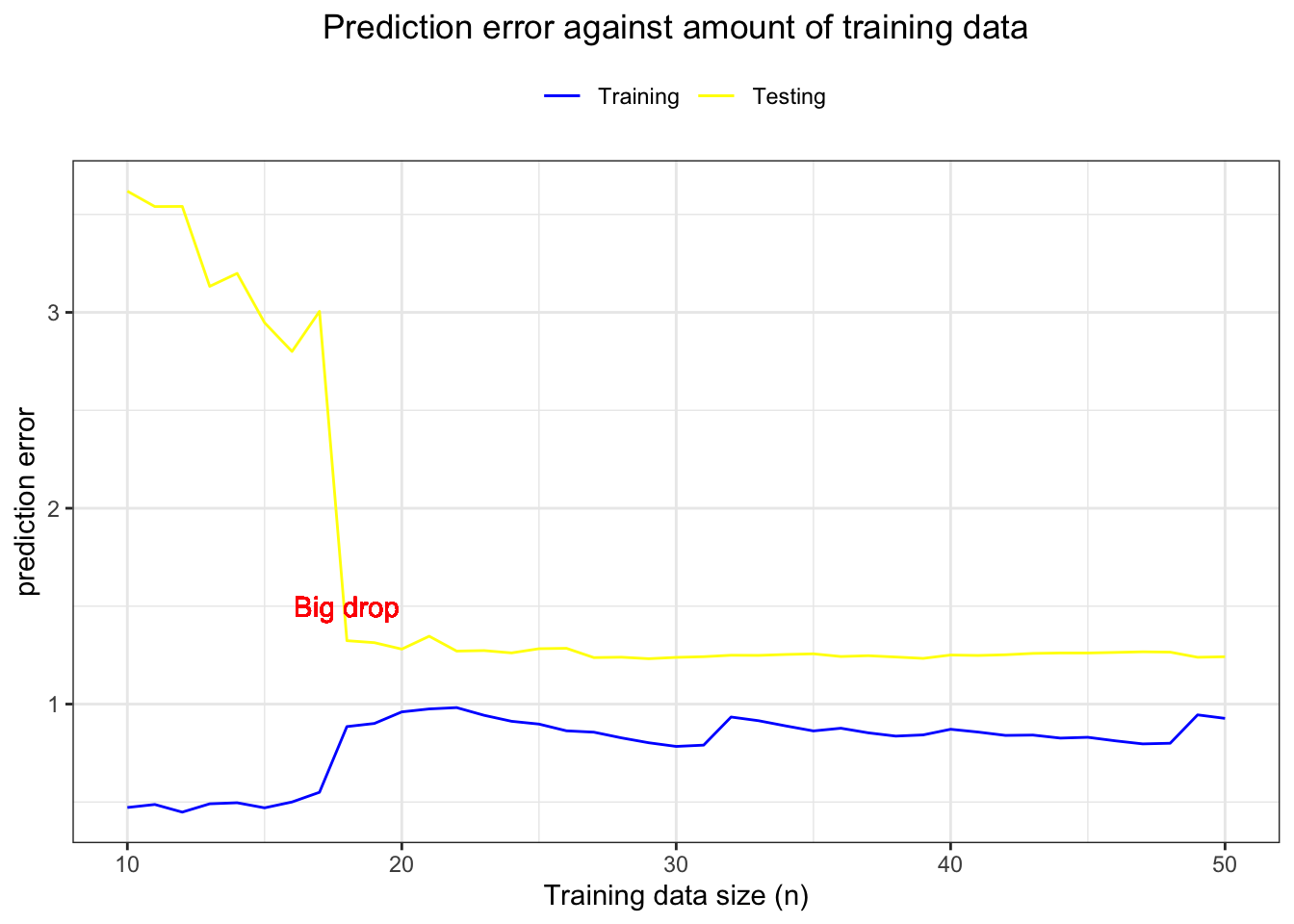

How do these errors behave when we keep increasing the training sample size? Let’s stick with the best model we found previously. We will train it on varying training sample sizes,

Then we plot the training sample size

training_n = c()

testing_n = c()

for (n in 10:50){

train <- sample[1:n,]

test <- na.omit(sample[n+1:450,])

reg <- lm(y ~ poly(x, 5), data = train)

pred_test <- predict(reg, test[,1])

training_n[n-9] = sum((reg$residuals)^2) / n

testing_n[n-9] = sum((test[,2] - pred_test)^2) / (450 - n)

}

obs_seq = seq(10, 50)

final_df = data.frame(cbind(obs_seq, training_n, testing_n))

ggplot(final_df, aes(obs_seq, training_n, colour = "Training")) + geom_line() +

geom_line(aes(obs_seq, testing_n, colour = "Testing")) + theme_bw() +

scale_colour_manual("",

breaks = c("Training", "Testing"),

values = c("blue", "yellow")) +

labs(title = "Prediction error against amount of training data",

x = "Training data size (n)", y = "prediction error") +

geom_text(x = 18, y = 1.5, label = "Big drop", inherit.aes = FALSE, colour = "red") +

theme(plot.title = element_text(hjust=0.5), legend.position = "top")

The training error increases with a bigger sample size - we are less prone to fit the noise when there is more available data. The testing error steadily decreases up to a point where it drops significantly (

Summary

- If we knew the joint distribution of

- Empirical risk approximates the actual risk better and better as the sample size increases.

- We neither want to underfit nor overfit the training data. The aim is to find the sweet spot in between.

- Complex patterns require more sensitive models to capture them. When a pattern is apparent, we do not need many training samples to generalise well.